Catching Corporate Crooks Needs Greater Priority

By Associate Professor Michael Legg, UNSW

SYDNEY: 14 January 2015 - Catching crooks comes before punishing crooks. Australia’s corporate regulator has been pushing for higher penalties to avoid Australia being a "paradise" for white-collar criminals. At the same time the Federal government has cut ASIC’s budget which is expected to substantially reduce ASIC’s proactive surveillance.

ASIC and the Federal Government would benefit from looking at the views of the new head of New York’s Department of Financial Services, Benjamin Lawsky, who oversees financial products and services. Lawsky, a former federal prosecutor, has observed that “perhaps individuals on Wall Street faced with competitive pressures and the lure of potential profits decide to cheat – in part – because they think they'll never get caught”.

Deterrence scholarship has found that the certainty of being apprehended and punished has a greater deterrent effect than the severity of the punishment. In the criminal law, courts have proceeded on the basis that deterrence is achieved not by harsher sentences but by “the impression on the minds of those who are persisting in a course of crime that detection is likely and punishment will be certain”.

However achieving certainty of detection and punishment is hampered by the complexity of the business environment, the need for due process and the significant resources available to many alleged contravenors who are large corporations and banks to fight regulatory action. To respond to these factors regulators need sufficient resources, including skilled and experienced personnel, coercive investigatory powers, a whistle blower regime and the will to pursue contraventions to the end.

Lawsky has also stated that he believes that regulators have not placed a high enough priority on their enforcement responsibilities.

Regulators in many spheres, including ASIC, have been encouraged to seek compliance first. This is part of regulation that employs an enforcement pyramid. The regulator advises, educates and negotiates with the regulated entity to assist them to prevent a contravention or to voluntarily take actions to respond to a contravention. A compliance approach can seek results quickly and cheaply. However, even with a contravention having been detected the certainty of punishment does not follow. An agreement to attend to the problem may be the only consequence that follows.

In contrast a deterrence strategy seeks to secure conformity with the law by detecting violations of the law, determining who is responsible for the violations, and penalizing those violators. Punishment seeks to inhibit future violations by those who have been caught, but it also serves as a lesson to others as to what happens to those who contravene the law. Heads on sticks sends a powerful message. But deterrence can be slower and more expensive as it will frequently require recourse to the courts. Consequently the regulator with a large remit and limited resources falls back on to compliance and starts to look for negotiated outcomes.

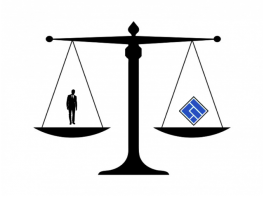

The regulator needs to be able to be both the cleric urging good deeds on his flock and the cop wielding handcuffs. Managing this split personality is undoubtedly difficult. Nonetheless, enforcement must be pursued so that those who are tempted to breach the law are dissuaded through fear of being caught and punished. Lasky terms it altering the calculus. Cuts to ASIC’s budget certainly alter the calculus but in the wrong direction – the chances of getting caught are reduced.

The law on the books and the penalties listed next to them are important, but they have no role to play unless ASIC can detect contraventions and follows through with legal action.

Add new comment