Red Lights Ahead for the G20? First Mover Problems Amongst Friends

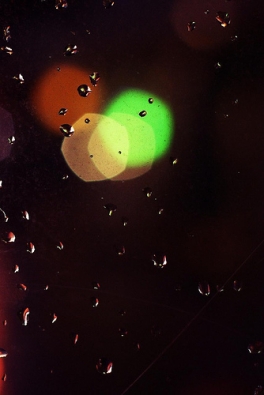

Periodically, the Secretariat of the Financial Stability Board (FSB) reports on progress made by G20 countries in implementing previously agreed financial regulatory reforms. It has introduced a traffic light system to provide a visual representation of that progress. The most recent FSB report, released on 19 June 2012, awarded the G20 members a collective ‘red light’, meaning the lowest level of implementation, in relation to two core reforms: design of effective bank resolution arrangements and the establishment of supervisors with sufficient independence, mandate, and tools to identify and address risks (supervisory independence).

The FSB report did not ‘name and shame’ the individual G20 members that have failed to implement the red light reforms nor did it suggest reasons for non-compliance. It does, however, raise an interesting and unresolved question. Why, after all the dislocation caused by the Global Financial Crisis and the design of an international architecture have core reforms not been implemented at national level?

The answer may well lie in the operation of ‘first mover’ problem. This term describes the tendency of governments to sign up to international standards so they are ‘in the club’, but as far as possible avoid implementing globally-agreed reforms that might restrict their ability to bolster the competitiveness of their financial sectors. This occurs because a government that moves first in introducing regulation that limits its influence over the financial system might be left at a disadvantage if others do not do the same. The problem is that if all or most governments think the same way, a prisoner’s dilemma emerges; everyone considers it in their collective best interest to introduce regulatory reforms, but no one wants to go first, and so ultimately no one acts and the system remains risky.

The red light reforms have the ingredients of the first mover problem. Most obviously, the reforms reduce the capability of governments to meddle with the financial system. A comprehensive bank resolution scheme means that a set procedure, often administered by a regulator, must be followed in the event of a failing bank, limiting government discretion. Likewise, an autonomous supervisor establishes an independent power base in the financial system that, in theory, can only be overridden by governments in certain situations, which further reduces government control over the financial system.

Governments may overcome the first mover problem and implement the reforms only if they can trust that others will do the same. This requires at least one actor to signal that it is willing to take certain steps if the others will follow. The different regulatory realities between members of the G20, especially the advanced markets (such as the US, UK and EU) and emerging markets, particularly China, means that this trust is unlikely to develop and signalling is unlikely to operate effectively.

Let’s start with advanced markets. Domestic pressure has built on governments of these markets to implement reform that resembles, to a degree, the red light reforms. For example, the US’ Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank) of 2010 established the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (BCFP), an independent agency designed to supervise banks, credit unions, and other financial companies in relation to federal consumer financial laws. This looks like an example of a supervisory independence red light reform, albeit a limited one given that the mandate of the BCFP does not extend to regulating wholesale markets. Even if limited however, the introduction of the BCFP suggests that domestic pressure might convince the US government to move further in relation to the red lights reforms if it could trust that others would do the same.

However why would these members do the same as the US in relation to the red light reforms, particularly China? This country has little incentive to implement the red light reforms and so reduce its control over the financial system. China’s economic model, in which a strong executive directs financial development with little regulatory constraint, appears to have assisted the country to avoid the worst of the financial crisis. In particular, its major banks remain far better capitalised than those of advanced markets, reducing its incentive to introduce strong bank resolution schemes.

Furthermore, China may be taking a different regulatory approach to the US. On 31 July 2012 the China Securities Regulatory Commission announced that it had promulgated the Interim Measures on the Supervision and Management of Integrity of the Securities and Futures Market (Measures), to take effect in September of this year. Interestingly, rather than focus on supervisory independence or bank resolution, the Measures consist of a legal regime designed to develop ‘integrity’ in the Chinese capital markets. The Measures work towards this goal through a variety of methods such as establishing a credit record system which permits the public to view an institution’s illegal and dishonest activities, and incentivising and encouraging integrity by supporting awards for institutions with strong credit records.

Unlike the Asian Financial Crisis, this time governments of advanced markets cannot use institutions such as the International Monetary Fund to force countries like China to reform their financial systems in line with the red light reforms. If no one can force anyone else to implement the red light reforms and no one wants to be the ‘first mover’, we have the prisoner’s dilemma; the US and other comparable advanced markets will not move given that China, by designing the Measures, may be taking a different approach to regulation and so is unlikely to follow. Ultimately no-one moves and the red light reforms remain on the G20’s wishlist.

At this stage it is difficult to read too heavily into the failure of G20 countries to implement the red light reforms. Perhaps all or most G20 countries are unable to implement the reforms given their complexity but intend to do so as soon as possible. However, sceptics of the coherence of the G20 may later point back to the FSB report as an early warning sign of the challenges in implementing substantive reforms across this disparate group. The FSB report may be alerting us to red lights ahead.

Add new comment