Repeating History? Financial Market Volatility, Pricing and Liquidity

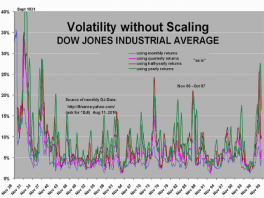

SYDNEY: 31 October 2014 - History has a way of repeating itself, which appeared to be a concern of the Reserve Bank of Australia’s assistant governor, Guy Debelle, when he spoke at the Australian and New Zealand Investment Conference on 14 October about market volatility and asset pricing. Debelle questioned why financial markets have exhibited dampened volatility despite a multitude of destabilising developments such as conflict in Eastern Europe and the Middle East and financial regulatory uncertainty in the US, Japan and Europe. Yet Debelle was clear that low volatility will not persist. He warned that “[w]hen volatility returns … it may well rise quite rapidly” at which point an asset sell-off, particularly in fixed income, “could be relatively violent when it comes”. It is noteworthy that Debelle couched the prospect of such events in the language of inevitability as opposed to hypothetical.

Debelle’s 2014 assessment of market volatility and asset pricing is reminiscent of the IMF caution in April 2007: “with volatility across asset classes close to historic lows and spreads on a variety of credit instruments tight, investors may not have adequately factored in the possibility that a ‘volatility shock’ may be amplified given the increased linkages across products and markets.”

This is indeed what happened when the market for mortgage-backed securities collapsed in late 2007, infecting the asset portfolios of banks internationally and precipitating the 2008/2009 global financial crisis.

This time around, Debelle’s assertion is predicated on several rationales. First, “one should never under-estimate the role of mechanical rules or mandates in driving market behaviour more than rational pricing.” In such a case, “there is a fair chance that volatility will feed on itself”. Moreover:

there are a number of investors buying assets on the presumption of a level of liquidity which is not there. As I said earlier, this is not evident when positions are being put on, but will become readily apparent when investors attempt to exit their positions. If you are a buy-and-hold investor focusing on the return on your investment, then secondary market liquidity is not really an issue (though it might affect your mark-to-market valuations on the way through). But there are probably a sizeable number of investors who are presuming they can exit their positions ahead of any sell-off. History tells us that this is generally not a successful strategy.

So is history repeating itself?

In his work on James M. Landis, Justin O’Brien provides a sobering assessment of political and market collective memory. He opines that the principal G20 concerns regarding too big to fail and reform of shadow banking and OTC derivative markets are not new economic or political problems. Yet they remain live issues due to a lack of political will to resolve them. O’Brien retraces the ‘New Deal’ financial market reforms led by Landis, adviser to the Roosevelt Administration, in the 1930s, which characterised the Great Depression recovery in the US and eventually became the model for financial market regulation around the world. At that time, too big to fail entities were utility companies that had become financial behemoths staunchly opposed to their regulation – similar to the regulatory resistance exhibited by some contemporary financial institutions. O’Brien contends that their immense economic and political power was overcome at that time, if only briefly, by regulatory action that had a “strong normative underpinning, informed by adroit administrative tactics, effective litigation strategy and resolute political backing.”

Whether the political landscape today is amenable to engaging in such financial/regulatory battles is a key question.

Certainly, there is growing recognition that securitisation can be restored to grace if it is regulated appropriately. The challenge is doing so in a coordinated and efficacious way that is cognisant of cross-border tensions.

Will Higgs cites six key areas of focus:

- the requirement for originators or other participants in the structuring of transactions to retain on their books a meaningful amount of the underlying risk;

- regulation of credit rating agencies;

- risk management and due diligence;

- securitisation reporting requirements;

- the treatment of resecuritisations; and

- OTC derivatives clearing and regulation.

In particular, the second point on Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs) is critical given that the gatekeeper function of CRAs in asset and risk pricing means they have a direct impact on the actions of investors, borrowers, issuers and governments. International developments in this space are extremely important for entrenching economic resilience, which is a cornerstone of the 2014 G20 agenda. To this end, the Washington G20 summit in 2008 resolved to ensure that “no institution, product or market was left unregulated at EU and international levels”. As part of Europe's response to those commitments, the European Parliament passed the EU Regulation on Credit Rating Agencies (Regulation 1060/2009), which has been in force since December 2010 and sets enforceable behavioural standards for CRAs, with an emphasis on transparency, independence and quality when rating sovereign states. It was amended in May 2011 to accommodate the creation of the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) which carries all supervisory powers over credit rating agencies. The current regulatory package, reinforces those existing rules on credit rating agencies, consists of Regulation 462/2013 and Directive 2013/14/EC.

However, Debelle’s concerns imply that improving one (albeit important) strand of market regulation may be insufficient given the hard lessons of the 2008/2009 financial crisis.

Part of the issue is the appropriate role of regulators as effective enforcers. In considering fraudulent asset management schemes in America, Robert Schwartz and Etay Katz argue that legal approaches such as the Hedge Fund Registration Act have responded to political pressure but may be insufficient to prevent future crises. The Act requires a higher number of unregistered US hedge fund advisers to register as investment advisers and increases disclosure obligations to the intended benefit of investors. Yet “disclosure is only as good as the entity giving it and… regulators have a hard time policing fraud where they only have self-reporting to go on.” The potential lack of independent compliance review within a firm and the continued scope for overlapping adviser and broker-dealer roles only exacerbate concerns. Schwartz and Katz consider alternative approaches under UK and Irish law and find that effective regulation requires external checks to protect against fraud, self-interest and self-dealing.

Indeed, the interrelated nature of modern financial institutions, rating agencies and asset portfolios, and the ambivalent national political landscape means that international political coordination is required to resolve and avert global crises. On this point, Dirk Schoenmaker provides a compelling perspective on banking supervision and resolution in Europe. He finds that the 2008-09 financial crisis highlighted the lack of an effective crisis-management framework for cross-border financial institutions, resulting in national interests taking priority over the interests of international financial stability. For example, in October 2011 national banking supervisors realised that additional capital was required to restore market confidence and liquidity in European banks. However, a divisive issue was whether the capital shortfall should be presented as an amount or a ratio. On the one hand, presenting it as an amount would increase bank lending; yet presenting it as a ratio would allow banks to sidestep capitalisation by simply deleveraging. The European Banking Authority and national supervisors eventually compromised by presenting the capital shortfall as a ratio to be applied to a Euro amount. The result was a sell-off of sovereign bonds and deleveraging.

In light of these experiences, recognition of globalised financial markets and systemic risk has been a powerful impetus for international regulatory reform. Elisabetta Bellini contends that calls for greater international coordination have reached a peak, leading some to suggest establishing a new international financial regulator, operating independently from governments. Such a body would be less constrained by politics, rival national interests, and lobbying. Yet these calls are highly cyclical and, as Bellini notes, the principal cyclical feature is political pressure. She argues that regulators tend to pay greater attention to political rewards than to the proper balancing of competing interests or the merits of a cost-benefit analysis - whether in times of economic uplift or downturn.

When market volatility returns and a ‘violent’ asset sell-off occurs, domestic and international regulatory bodies may need to respond quickly and effectively given that, as Debelle points out, “exits tend to get jammed unexpectedly and rapidly”. Yet the 2008/2009 financial crisis made clear that proactivity is preferable when key warning signals are brought to light. The question is whether we have already forgotten those lessons.

The author wishes to thank Sherif Alam, CLMR intern, for research assistance for this article.

Add new comment